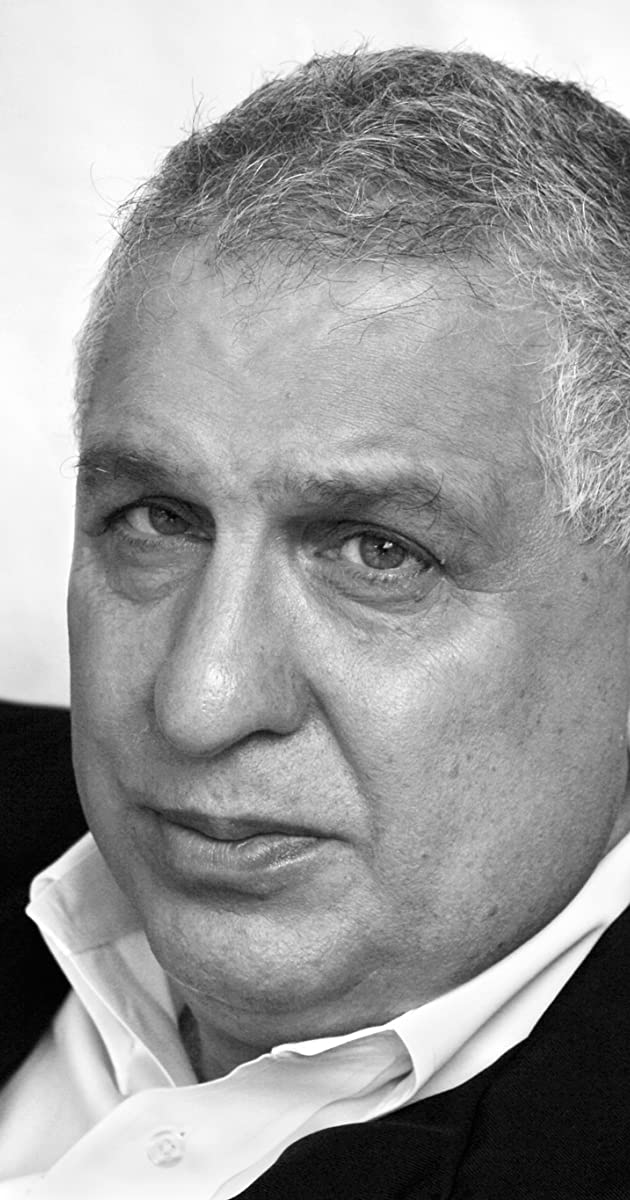

His documentaries helped spur a rebirth of non-fiction film in the 80s & garnered wide critical success. But until 2003’s “The Fog of War,” Morris was shunned by the Academy Awards.

Morris’ first two films won much acclaim (Gates of Heaven (1978) and Vernon, Florida (1981)). In the second movie, Morris intended to explore “Nub City,” the town known for residents trading limbs for insurance settlements, but death threats (and some other equally fascinating locals) morphed Morris’ focus into profiling other citizens instead.

After his first two films, Morris found financing for new projects scarce, so he turned to a unusual source of income – working as a New York private detective. Finally, after 6 years, he moved into feature-length, (and more serious projects) with The Thin Blue Line (1988).

Errol Morris cites his detective experience as providing new skills for his investigative filmmaking, most notably in “The Thin Blue Line”, which resulted in a wrongfully convicted man being freed from a lifetime sentence in Texas after serving 13 years for a policeman’s murder. Morris persuaded the real murderer to help free the innocent man. The real killer was subsequently executed for a unrelated murder.

Morris uses techniques not traditionally seen in documentaries, to make his films more dramatic and diverse, such as the Thin Blue Line’s incredibly eerie Philip Glass score, and the haunting reenactments of the policeman’s murder. Thin Blue Line’s multiple points of view have drawn favorable comparisons to Kurosawa’s ground-breaking cinema classic, Rashomon (1950). His own striking, innovative film style is very influential. Like Alfred Hitchcock, Morris knows how to create careful doses of emotional reality, which can have much more impact on a viewer than a literal reality can be on film.

Technical problems forced Morris to insert his voice as an interviewer for the first time, at the end of The Thin Blue Line, and he’s experimented with using himself in his documentaries since. Morris incorporated his reaction to his parents’ recent deaths in Fast, Cheap & Out of Control (1997).

Morris feels his interviewing of subjects, has been greatly enhanced in his later work, by devising the Interrotron (terror and interview). It’s two cameras, one on Morris and one on the interviewee. Each sees the other’s images staring directly into the lens, to give the audience the appearance the subject is talking directly to them.

While his work explores a wide range of subjects, Morris has stated his films break down into “Completely Whacked Out” and “Politically Concerned.” Many focus on people with strong, unusual obsessions. His cable documentary series First Person, was especially effective presenting with great sympathy, power and humor, compelling individuals such as Temple Grandin, an animal scientist who has autism. Grandin designs animal slaughterhouses to be humane.

Fred Leuchter, the subject of Morris’ film, Mr. Death: The Rise and Fall of Fred A. Leuchter, Jr. (1999) was slated to be one of the people profiled in Morris’ “Fast, Cheap & Out of Control”, but Morris decided putting Leuchter in the same film would overpower the other portraits. Leuchter’d been dubbed “The Florence Nightingale of Death Row” for his career of making prisoner execution methods more humane, was invited by a Holocaust denier who was on trial, to examine the site of the Auschwitz death camp. Way out of his league, Leuchter’s faulty, amateurish research led him to claim that Auschwitz could not have been used for executions. “Accidental Nazi” was considered as a title for the film. Morris prefers characters who are puzzling.

The film brought Morris (who’s Jewish) much criticism and attention. One of Morris’ recurring themes is the powerful contrasts between how his subjects view themselves, and how audiences view them. The witty Morris revels in his own off kilter humor, iconoclasm, and extreme skepticism when he’s being interviewed.

Morris had problems when he ventured into directing a Hollywood fiction film as did his contemporaries Michael Moore, Joe Berlinger, and Bruce Sinofsky. The Dark Wind (1991) was held up by the studio for 2 years, then released on video. It was an adaptation of a Tony Hillerman mystery novel, executive produced by Robert Redford. Morris has continued entirely with non-fiction, though many of his subjects are much stranger than fiction anyway.

He has taken on difficult subjects, such as A Brief History of Time (1991), about the paraplegic physicist Stephen Hawking, illustrating Hawking’s revolutionary theories, and comparing the paralyzed scientist’s own rich interior world periled by ALS, with the complex, dying universe Hawking limns.

Morris’ film The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara (2003), examines the architect of the U.S. war in Vietnam, former Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara. Morris’ academic training in philosophy and history shows in his documentaries’ vast depth. While getting a history degree at University of Wisconsin, Morris explored doing a film on notorious local murderer Ed Gein (Gein was the basis for Psycho (1960)). Morris also studied at Princeton and University of California – Berkeley.

Morris’ directing career started while he programmed shows at the California’s Pacific Film Archive. A newspaper headline spurred his first film “Gates of Heaven,” revealing with bizarre developments in 2 widely contrasting pet cemeteries. The uncut film confounded editors, such as Academy Award nominee David Webb Peoples (Unforgiven (1992)). German film director Werner Herzog bet Morris that the film would never get made. At Berkeley, Herzog settled the bet on stage in an incredible display, as documented by director Les Blank (whose son ‘Harrod Blank’_ is also an acclaimed documentary filmmaker) in Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe.

Morris, who received a MacArthur Foundation genius grant, says none of his films have made him money, so he directs commercials, and won an Emmy in 2001. A series of campaign ads he did for John Kerry was little shown. Morris’ much-criticized approach was to Interrotron actual Republicans and conservatives who had switched to support Kerry, versus George W. Bush. Morris has an occasional feature in the New York Times ruminating on the power and meaning of photos.

Opening April 2008 is his new feature, Standard Operating Procedure (2008), which explores abuse in the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. The film is accompanied by a book of on-set photos of Morris’ productions.